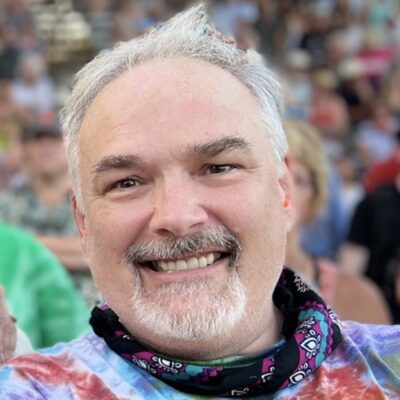

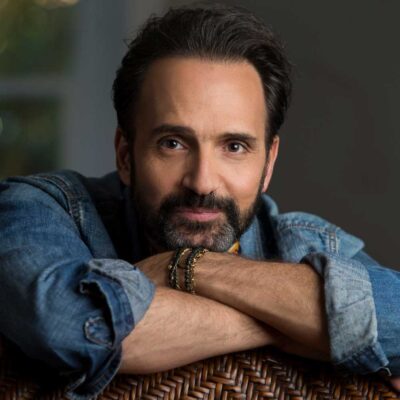

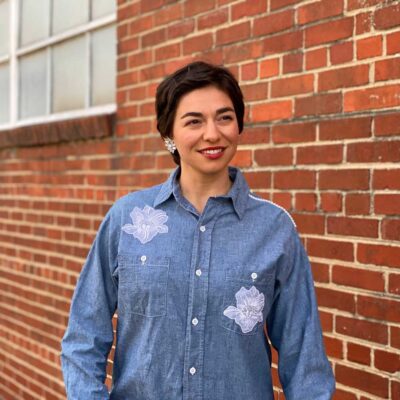

Sara Thomsen

(Genre: Folk; Location: Duluth, MN)

Sara Thomsen is a staunch supporter of struggles for human dignity and ecological sustainability. Her songs have earned her recognition in national songwriting competitions. She is the founder and artistic director of the Echoes of Peace Choir, a non-audition community choir in Duluth, Minnesota, with a repertoire of world music and a membership of 70+ voices. Sara is founder and director of the Echoes of Peace non-profit, which works to expand and develop the work of examining critical social issues using music and the arts to build and bridge informed, engaged, and caring communities

A note about "Water is Life" (from Sara)

In August of 2016 I traveled to Standing Rock, North Dakota to stand in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and the many tribes, nations, native and non-native people coming together to protect the land and the Missouri River water threatened by the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

I was compelled to go, in part, because I am originally from South Dakota. The Missouri runs straight through the middle of the state. Our family crossed it every year as we traveled the state from east to west to visit my grandparents in the Black Hills. As kids we made a contest over who could hold their breath the longest as we crossed “the wide Missouri.” As a descendent of European immigrants, I also felt compelled to go. I was aware of the history of genocide and oppression against indigenous peoples of this land and how those historical injustices continue to play out in present day realities. I knew that history benefited my farming ancestors (and thereby me). It felt important as a white person to take a stand of solidarity in some way, shape, or form.

I was compelled to go because the fight to protect the water is at the heart of our struggle to protect this earth from the human led forces that deign to destroy it. I watched how the movement grew from a small group of Standing Rock Sioux youth taking a stand to protect their land to a worldwide movement. It was being there, in that place and at that time, that this song came to be.

On my last morning at Standing Rock, I was busily packing things up inside my tent when I suddenly heard a meadowlark singing. I stopped everything and just listened. It was right outside the door of my tent and it felt like it was singing directly to me. And then, in whatever way this happens, I heard the words “Be a lark from the meadow. Be a lark from this meadow.” It flew away and I carried on packing. A few moments later (still in the tent packing up) I started repeating those words. As I did, it appeared again, singing right outside my tent, as if to emphasize “Yes, that's what I said. Get on it!” That morning moment mixed in and around all the rest of my experience being at Standing Rock. On the eight hour drive back home, this song was born.

I had doubts about whether I should be sharing the song beyond the moment of it’s birth. Who am I, a white woman, a descendent of Western European farming settlers, to be singing this song. Was it appropriate, inappropriate, was it appropriation? All these questions whirled through my heart and head. And yet the memory of the meadowlark, singing outside my tent prodded me.

The first person with whom I shared the song was Lakota. A professor of mine from my college years. He was grateful that I shared the song with him and responded by sharing a story: “You may have heard in class, my story of the medicine tree, in which a small warrior dressed all in yellow sings a song which heals a man and then all the ancestors of the people now on the Yankton reservation. An important aspect of that healing revelation is that true medicine comes only from where one is... and the message comes from a meadowlark.”

I shared the song with my friend Sharon Day who is Ojibwe. She told me this: “Some songs just drop into that place where music lives and this one by the meadow lark. Who are we to question why? Sing it, it's beautiful and it’s your land too, and the water belongs to all creation. Migwetch for sharing.” A year following the events at Standing Rock, I was invited by Sharon to join her on the Missouri River Water Walk she was leading. It was on that walk that Sharon added the “Wayo wayo way ya” part of the song.

In this way, I continued to share the song and in that sharing the song itself grew and evolved. After my sharing this song at choir practice, Jeremy Davis, of Lakota and Anishinaabe heritage, came up to me afterwards and encouraged me to add the Lakota phrase “Mitakuye Oyasin” (All my relations) to the song. I feel a certain responsibility to continue sharing the song, and the story behind the song.

- Sara